The Conflicts Between U.S. Sanction Laws and the LC Independence Principle:A Case Study of North Korea’s Deceptive Shipping Practices

Second Author: Catherine Shi, Head of Overseas Business of DKL, Of-counsel of DHH Washington DC Law Office

Introduction

Under the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credit 600 (“UCP 600”) which comes into effect on 1 July 2007, the issuing banks or confirming banks (“Banks”) of a letter of credit (“LC”) shall examine the presented documents based on the doctrine of strict compliance. Banks are refrained from digging into the underlying transaction, in order to maintain certainty regarding international payment. Banks should unconditionally honor their LC undertakings if the presented documents comply with the LC. That is called the independence principle of the LC (“Independence Principle”).

As the United States of America (“U.S.”) first imposed sanctions against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (“North Korea”) in 1950, the North Korea-related sanction laws had become the most important parts of the U.S. sanction system. To evade the sanctions, North Korea had employed variable shipping practices.

Consequently, if Banks insist on the Independence Principle and pay a LC with the sanctionable underlying transaction, they will face harsh punishment by the U.S. government. On the other hand, if Banks make extra effort to investigate the underlying transactions, the Independence Principle will be damaged.

This article tries to solve the above dilemma for the Bank. The discussion will be based on the Banks' obligation under the U.S. sanction laws and the LC rules.

I. Summary of the U.S. Sanction Regime Targeting North Korea

1. Legal Framework

The U.S. has been imposing economic sanctions against the North Korea since 1950.

The current North Korea sanctions program of the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the U.S. Department of the Treasury (“OFAC”) began in 2008 when the U.S. President (“President”) issued Executive Order (“E.O.”) 13466, where the President declared a national emergency to deal with the threat to the national security and foreign policy of the U.S. constituted by the existence and risk of the proliferation of weapons-usable fissile material on the Korean Peninsula, and continued certain restrictions with respect to North Korea that previously had been imposed under the authority of the Trading With the Enemy Act. ( See North Korea Sanction Program, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/nkorea.pdf)

In 2010, President Obama issued E.O. 13357, which created the first North Korea -specific sanction program of the U.S. The following E.O. 13687 and E,O. 13722, also issued by President Obama, expanded the sanctions targeting North Korea’s governmental assets, financial activities, and “significant activities undermining cybersecurity.”

In 2016, the U.S. Congress passed the Summary of the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016 (“NKSPEA”). Following NKSPEA, the U.S. Congress also passed additional legislation, the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (“CAATSA”), in 2017, which among other things, imposed new sanctions on Iran, Russia, and North Korea. NKSPEA and CAATSA require the President to sanction entities contributing to North Korea's weapons of mass destruction program, arms trade, human rights abuses, or other illegal activities. They also impose mandatory sanctions on entities involved in North Korea's mineral or metal trade.

On 21 September 2017, President Donald Trump issued E.O. 13810, allowing the U.S to cut from its financial system or freeze assets of any companies, businesses, organizations, and individuals trading in goods, services, or technology with North Korea. Aircraft or ships entering North Korea are banned from entering the U.S for 180 days. The same restriction applies to vessels that conduct ship-to-ship (“STS”) transfers with North Korean ships.

STS transfers mean transferring cargo from one ship to another while at sea. By STS transfers, the vessels can deliver sanctionable goods to or from North Korea-related vessels without docking at a North Korean port.

The abovementioned statutes and E.O.s assign the authority to enforce the sanctions to variable federal agencies. Among those agencies, the OFAC is the most important institute which administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions based on U.S. foreign policy and national security goals against targeted foreign countries and regimes, terrorists, international narcotics traffickers, those engaged in activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and other threats to the national security, foreign policy or economy of the U.S. OFAC codified the authorities mentioned above in its regulations published as the 31 CFR Part 510 - North Korea Sanctions Regulations.

2. Prohibited Transactions

Among others, the U.S. sanction laws block certain property and interest in property of North Korea or its nationals from entering into the U.S. Further, the U.S. sanction laws prohibit U.S. persons from engaging in the following activities:

o transactions involving North Korean vessels, including registering vessels in North Korea, obtaining authorization for a vessel to fly the North Korean flag, and owning, leasing, operating, or insuring any vessel flagged by North Korea;

o importing from North Korea to the U.S. or exporting to North Korea from the U.S. goods, services, and technology, directly or indirectly, without a license from OFAC or applicable exemptions;

o investing in the North Korea without a license from OFAC or applicable exemption; and

o any approval, financing, facilitation, or guarantee by a U.S. person of a transaction by a foreign person if the transaction is performed by a U.S. person or within the U.S.( See North Korea Sanction Program, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/nkorea.pdf)

II. Evasion: Sanctionable Shipping Practice Employed by North Korea

1. The Evasion

The U.S. prohibits trade and other transactions directly or indirectly with North Korea. In order to evade the embargo, North Korea has been engaged in variable deceptive shipping practices, such as physically altering the vessel identification, STS transfers, falsifying cargo and vessel documents, disabling automatic identification system (“AIS”), manipulating AIS, etc. (“Evasion”)

AIS is the system transmitting a vessel’s identification and positional data. By disabling or manipulating the AIS, North Korean-related ships can conceal their origin or destination. ( See North Korea Sanctions Advisory, issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury on February 23, 2018)

[source: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/dprk_vessel_advisory_02232018.pdf]

2. Shipping documentation may not be affected by the Evasion

Cargo and vessel documents include the bill of lading, certificate of origin, invoices, packing list, proof of insurance, lists of last ports of call, etc. Those documents are essential to ensuring the parties, goods, and vessels involved in a given shipment. Most of the LCs require the beneficiary to present those documents to the banks when drawing on the LC. By deploying deceptive shipping practices, North Korea obfuscates the identity of the vessels, the goods being shipping, and the origin or destination of the cargo. However, the resulted cargo and vessel documents may seem perfectly legitimate and genuine. In fact, to keep the vessel documents looking legitimate is the essential purpose of the evasion practices.

III. Banks’ Dilemma: Conflicts between the Sanction Laws and the Independence Principle

1. Banks’ Obligation and Liabilities Under the U.S. Sanction Laws

A. Non-U.S. banks may be the target of U.S. sanction laws

Traditionally, the OFAC imposes sanctions on U.S. persons. U.S. persons include individuals that are U.S. citizens and U.S. permanent residents, regardless of their location; legal entities organized within the U.S. and their foreign branches, and any individual or entity physically located in the U.S. ( OFAC FAQs: General Questions: Question 11: Who must comply with OFAC regulations?)

a. The non-U.S. bank is a subsidiary of a U.S. person

This is the most straightforward scenario under the definition of “U.S. person”.

b. The non-U.S. bank has a business presence in the U.S.

Usually, banks engaging in the business of international commercial finance will consider establishing a branch or representative office in the U.S. If a non-U.S. bank has such physical presence in the U.S., it is a U.S. person by the definition of “U.S. person”.

c. The relevant financial transaction is carried out via the U.S. financial system or using U.S. dollars.

It is well established that a non-U.S. bank avails itself to the U.S. jurisdiction if it engages in business transactions in U.S. dollars. In the case of BNP Paribas (“BNP”), a French bank that was accused of providing financial services to support commercial transactions with Iran, it is found sanctionable because of its availing of the U.S. financial system (See Department of Justice release at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/bnp-paribas-agrees-plead-guilty-and-pay-89-billion-illegally-processing-financial). Other examples could be found in the case of Commerzbank AG (See Department of Justice release at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/bnp-paribas-agrees-plead-guilty-and-pay-89-billion-illegally-processing-financial) and the case of Standard Charter.

In those cases, the non-U.S. banks are subjected to the U.S. sanction laws because of the finding of adequate contacts (Adequate contacts or minimum contacts is a term used in the U.S. law of civil procedure to determine when it is appropriate for a court in one state to assert personal jurisdiction over a defendant from another state.) between such banks and the U.S.d. Secondary Sanction

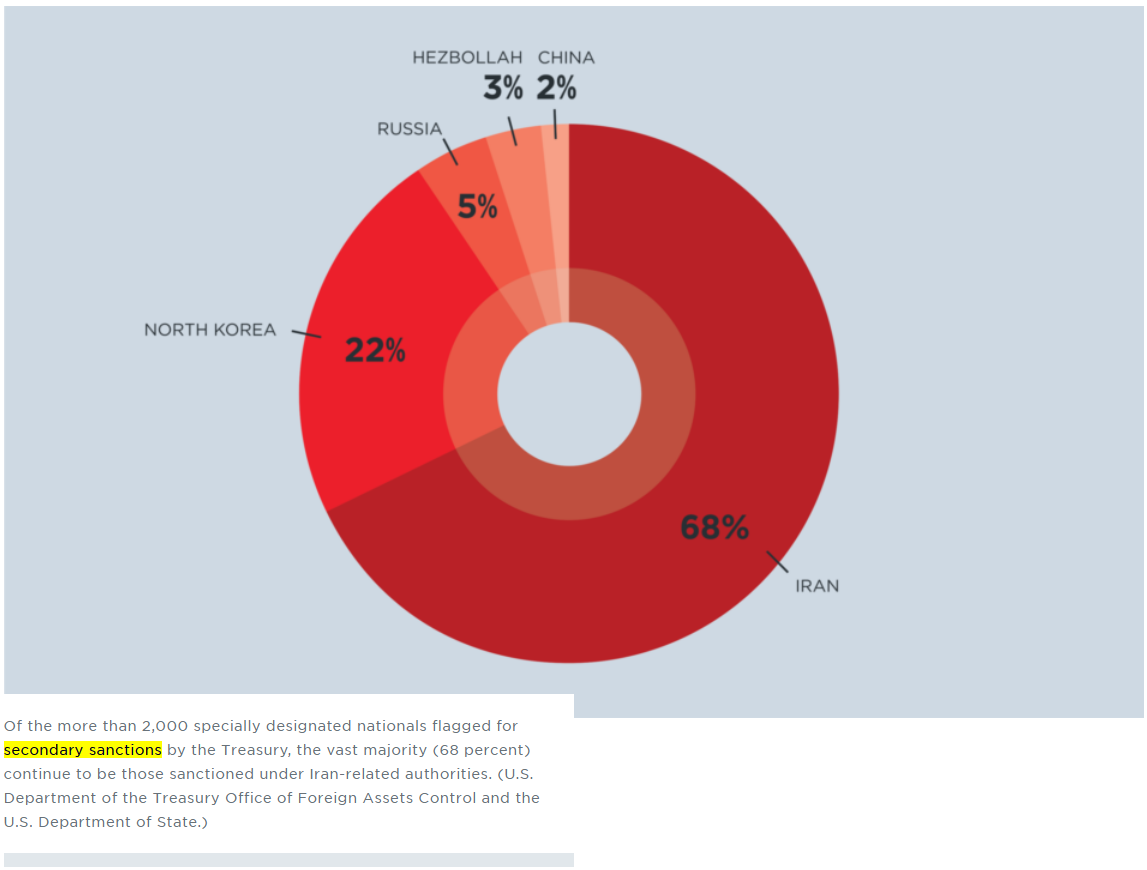

Under the so-called “Secondary Sanctions” scheme, which mainly imposes sanctions to non-U.S. persons and entities who lack a U.S. nexus, even if a non-U.S. bank that is not qualified as a U.S. person nor has any nexus with the U.S. could be a subject of the U.S. sanction laws. Typically, Secondary Sanctions prohibit a non-U.S. person from engaging in any activity that benefits a sanctioned country. The U.S. has imposed several secondary sanctions upon individuals and entities who involved in transactions with North Korea.

[source: https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/sanctions-by-the-numbers-u-s-secondary-sanctions]

E.O. 13810 authorized the imposition of sanctions on foreign financial institutions that “knowingly conducted or facilitated any significant transaction in connection with trade with N. Korea” or “knowingly conducted or facilitated any significant transaction on behalf of” certain persons who have been designated for sanctions ( §4(a)(i) , (ii) of E.O. 13810).

After the implementation of E.O. 13810, the OFAC imposed secondary sanctions upon several foreign financial institutions, shipping agencies, and import-export companies for their involvement in business transactions that benefit North Korea. For example, on January 24, 2018, Jong Man Bok, representative of Ryonbong Bank in Dandong, China and Ri Tok Jin, representative of Ryonbong in Ji’an, China, were added to the SDN List as the consequence of the secondary sanctions (See Department of Justice release at: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0257).

In conclusion, a non-U.S. bank, no matter whether it has requisite nexus with the U.S. or not, can be the subject of the U.S. sanction laws. For a bank engaging in international commercial finance, the risk is even higher.

B. Elements of banks’ violation

Pursuant to Section 4 (a) of E.O. 13810, any foreign financial institution is prohibited from knowingly conducting or facilitating any significant transaction in connection with North Korea, which is prohibited by the sanction laws.

Accordingly, a foreign bank should be punished for the violation of the sanction laws if it “knowingly” commits the forbidden activities. Section 8 (f) of the E.O. 13810 defines “knowingly” as “has actual knowledge, or should have known, of the conduct, the circumstance, or the result”.

a. Actual Knowledge

If a bank has actual knowledge that the LC is involved in a sanctionable transaction, it’s punishable under the E.O. 13810.

However, the government may encounter difficulties in proving the banks’ “actual knowledge” of the sanctionable nature of the underlying transaction. In other words, banks are safer under the “actual knowledge” theory.

b. Constructive Knowledge

Alternatively, the government could use the objective standard of constructive knowledge to prove the intent element of banks’ sanctionable activities. If a bank could obtain knowledge by exercising reasonable diligence, the laws presume that the bank should have known the sanctionable nature of the transaction. Thus, the bank may be punished for knowingly violating the sanction laws.

Thus, the constructive knowledge theory imposes the duty to look into the underlying transactions upon banks. Banks should employ due diligence to avoid the presumption of constructive knowledge.

However, do banks have the right to check the underlying transactions under the independence principle of LC?

2. The Independent Principle

LCs are referred to as "Special Contracts" because they are not governed by common law but by a set of special rules (The Fifth Circuit, in East Girard Sav. Ass'n v. Citizens Nat'l Bank & Trust Co., 593 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1979), stated that a LC is ‘simply not an ordinary contract. The LoC is a unique device developed to meet specific needs of the marketplace.’ Id. at 603. See also J. DOLAN, THE LAW OF LOCS: COMMERCIAL AND STANDBY CREDITS 2.01, 2.02 (1984).) Among those rules, the Independence Principle is a chief one.

According to the Independence Principle, a LC is separated from and independent of the underlying transactions. By keeping LCs independent and insulated from the disputes over the performance of underlying contracts, LCs can function as a swift and reliable payment method for global trade and investment.

A. The Banks’ Undertaking

Article 4 of UCP 600 provides that “a credit by its nature is a separate transaction from the sale or other contract on which it may be based.” Accordingly, if the presented documents are complied with the stipulation of the LC, the issuing bank, confirming bank, or any other nominated bank should pay the credit amount to the beneficiary regardless of the underlying contractual disputes (See Article 7, 8, 15 of UCP 600.).

B. “On Their Face” Examinations

Article 14 of UCP 600 provides that banks “must examine a presentation …. appear on their face to constitute a complying presentation”. Traditionally, the term “on their face” was interpreted as that banks should NOT perform any further inquiry or investigation beyond the presentation. Accordingly, banks should only examine the presented documents and pay no attention to whether the documents were counterfeit, valid, or complete.

Practically, the “on their face” examination standard is the “gold standard”, which is not only because of the express provisions of UCP 600. In fact, an examination standard higher than “on their face" standard will require more sophisticated examiners. As a result, only examiners with expertise in almost every industry can be competent to do that job. It is not only uneconomic but also impractical in considering banks’ enormous workload of the documents’ examination.

In sum, banks have no duty nor right to investigate the underlying transaction under the Independence Principle.

3. The Conflicts of Sanction laws and the Independence Principal

As discussed above, banks are refrained from investigating the underlying transactions of LCs. However, banks cannot afford to stick too much on the independence principle in considering the potential harsh punishment.

A. The Enforcement and Consequence of the Sanctions laws

a. the Enforcement

The U.S. sanction laws impose legal liabilities on banks if they knowingly aid or abet North Korea by providing any financial services.

To enforce the sanction scheme against North Korea, the OFAC requires financial institutions to facilitate strict internal compliance programs to “prohibit or reject unlicensed trade and financial transactions with specified countries, entities, and individuals”.(See BSA/Anti-Money Laundering Examination Manual - Office of Foreign Assets Control (July 2006)) Banks are required to apply “judgment and take into account all indicators of risk” to assess the risk of violation related to commercial LCs (See Id.). Specific methods of internal control, including but not limited to “Identifying and reviewing suspect transactions”, “Updating OFAC lists”, and “Screening ACH transactions” are mandatory (See Id.). Banks are required to investigate "suspect" transactions. Further, the OFAC regulations require banks to report the “suspect transactions” to the OFAC and reject the demands of payment.

b. Consequence of violation

OFAC establishes a two-track approach to penalty assessment: one for “egregious” cases and one for “non-egregious” cases.

OFAC will determine whether a case is “egregious” based on an analysis of several “general factors” it sets out in the Guidelines. Four of these factors will be given substantial weight in determining whether a case is “egregious”:

o willful or reckless violation of law;

o awareness of the conduct at issue (including reason to know);

o harm to sanctions program objectives; and

o individual characteristics of the entity(ies) involved. Particular emphasis will be placed on the first two factors identified.

OFAC may impose civil monetary penalties of up to the greater of $250,000 or twice the amount of the underlying transaction against any person who violates, attempts to violate, conspiracies to violate, or causes a violation. Upon conviction, criminal penalties of up to $1,000,000, imprisonment for up to 20 years, or both may be imposed against the violator.

Moreover, OFAC may add the violator to the SDN list as a secondary sanction. If a non-U.S. bank is on the SDN list, it will be cut off from the U.S. financial system. That almost means the death sentence of the bank’s international business.

B. The Wrongful Dishonor

On the other hand, UCP 600 and other LC rules, such as ISP 98, URDG 758, and U.S. UCC Article 5, require banks to honor their unconditional obligation of payment if the presentations comply with the LCs "on their face". Banks are refrained from doing any additional investigation beyond the presentation.

Thus, banks are facing the “Catch 22” problems when dealing with LCs related to sensitive parties, goods, and geographic areas. On the one hand, if the participants or goods of the underlying transactions are affiliated with Russia, P.R. China, Japan, Hong Kong SAR, or Singapore, banks face a higher risk of being punished by the U.S. government. Therefore, it is difficult or impossible to know the real nature of a transaction by “on their face” examination.

That is particularly true when dealing with LCs related to North Korea’s deceptive shipping practices. For example, prima facie, the STS transfers may not lead to forged bills of lading or other vessel documents. In fact, the essential purpose of North Korea’s deceptive shipping practices is to make the papers perfectly legitimate “on their face”. Consequently, it is more than often that the shipping documents are perfectly legitimate while the underlying transaction is a violation of the sanction laws.

In order to enforce the sanction laws, OFAC requires the banks to dig much deeper into the underlying transactions than the Independence Principle requirement.

If banks insist on the Independence Principle and only examine the documents “on their face”, they will be in big trouble with the U.S. government sooner or later.

On the other hand, if banks dishonor the LC because the LC is somehow related to "suspect transactions", they will be sued for wrongful dishonor by the beneficiary or other stakeholder of LCs.

Thus, Banks need to find the middle land to protect themselves from U.S. sanctions and civil suits.

IV. Price Must be Paid: How Deep Should Banks Dig into the Underlying Transaction?

As mentioned above, banks may become targets of sanction schemes if they were found guilty of knowingly aiding or facilitating North Korea’s sanctionable activities. The regulations issued by OFAC encourage or require banks to conduct additional investigation into the underlying commercial transactions of the LCs. However, if banks dig too deep into the background transaction, the independent nature of LCs would be destroyed. Consequently, the global commercial payment system would be jeopardized greatly.

Fortunately, banks can defend themselves by showing their lack of constructive knowledge. Constructive knowledge is presumed by law if banks can obtain the knowledge through reasonable due diligence. Thus, if banks can show that they have practiced reasonable due diligence, they may have a better chance to be off the hook.

It may not be "sufficiently reasonable" if foreign banks just follow their normal due diligence program. That is especially true when the underlying transactions involve sensitive parties, goods, or geographic areas. An enhanced due diligence scheme is necessary.

1. Know Your Customs’ Custom (“KYCC”)

Pursuant to the Patriot Act 2001, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) proposed the Know Your Customer (“KYC”) requirements in 2004. Accordingly, banks shall use reasonable diligence to ensure and retain the identity and associated risks when maintaining a business relationship with a customer or client.

However, because numerous participants are involved in the underlying transactions of LCs, some parties are not the direct customer of Banks. Banks may act as the issuing bank, negotiating bank, confirming bank, advising bank, accepting bank, discounting bank, reimbursing bank, or paying bank. Usually, the applicant of an LC is the customer of the issuing bank, but it is not necessarily the customer of the negotiating bank or the paying bank. Conversely, the beneficiary is usually the customer of the negotiating bank, but the issuing bank may have no business relationship with the beneficiary.

The transferrable LC makes things more complicated. By transferring the credit, the beneficiary transferred its LC right to a third party. Sometimes, Banks have no clue of who is the ultimate payee of the LC.

Thus, the traditional KYC program is not sufficient to mitigate the risk of a potential violation of the sanction laws. Before providing financial services and honoring their LC undertakings, banks should screen every relevant participant of the underlying transaction to know the identity of the customer’s customer.

2. Higher Risk Goods

When the LC is dealing with higher-risk goods (for example, weapons, nuclear material, or semi-conductors, etc.), FFIEC's BSA/AML MANUAL requires banks to pay more attention to the documents than merely applying the “on-their-face” examination ( See RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH MONEY LAUNDERING AND TERRORIST FINANCING,https://bsaaml.ffiec.gov/manual/RisksAssociatedWithMoneyLaunderingAndTerroristFinancing/19). Particularly, red flags should be raised when the goods appear to be over or undervalued, double invoiced, partially shipped, or use fictitious goods names.

3. Sensitive Geographic Places

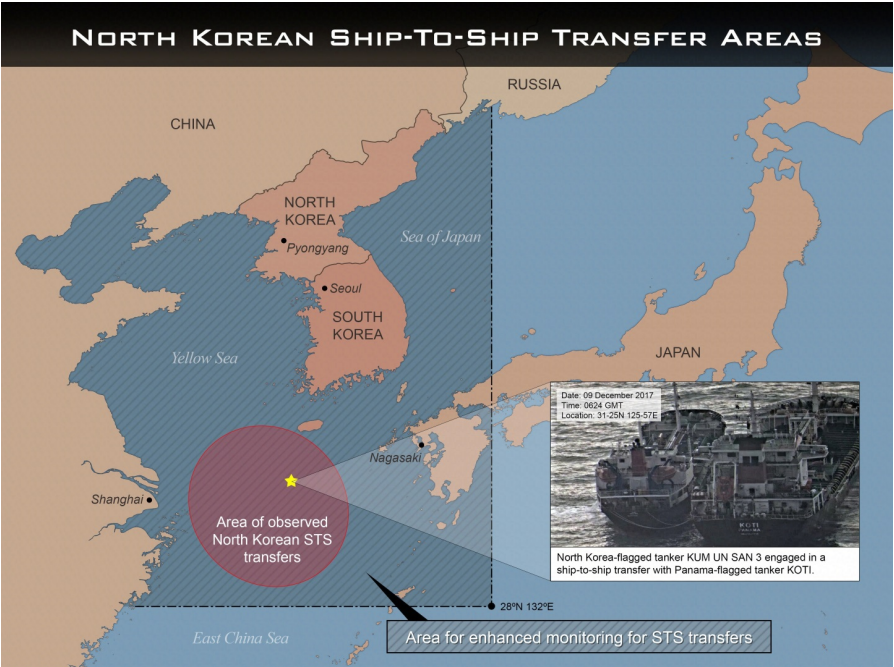

The following map shows areas where North Korean STS transfers commonly occur(Updated Guidance on Addressing North Korea’s Illicit Shipping Practices, Department of the Treasury, March 21, 2019):

[source: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/05142020_global_advisory_v1.pdf]

As the map shows, most of the North Korean STS practices occurred in the areas of the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the Sea of Japan. Thus, if the shipping documents show that the goods are shipped from the neighboring ports of those areas, more attention should be paid.

In sum, the enhanced internal compliance and the sanction clause may burden the banks and their clients. However, in considering the more and more strict U.S. sanction against North Korea, those are the price that must be paid.

V. Banks’ Defenses Against Claims of Wrongful Dishonor

According to UCP, ISP 98, URDG 758, and other LC rules and laws, the issuing bank must honor the LC if the presented documents comply with the stipulation in the credit (See § 7a, UCP 600). The confirming banks have the irrevocable obligation to honor or negotiate a complying presentation if they add confirmation to the LC.

Consequently, if banks dishonor the LCs because they found the underlying transaction is sanctionable under U.S. sanction laws, they could be sued by the beneficiary, the applicant, the transferee of a transferrable LC, or other stakeholders. Banks may raise the following defenses against the claims of dishonor:

1. Fraud Exception

The fraud exception to the Independence Principle is well established by case laws. Under the fraud exception, banks can ask the courts to issue injunctive orders to stop payment. Basically, the fraud exception allows the banks to dishonor under very rare circumstances.

However, the threshold to successfully raise the fraud exception defense is very high. Also, the required elements of the fraud exception are different in different countries.

In 3Com Corp. v. Banco do Brasil, S.A., the U.S. court held that dishonor due to fraud is proper where a draw has no basis in fact and represents a fraud in the transaction, or where a drawdown would amount to an outright fraudulent practice by the beneficiary (See 3Com Corp. v. Banco do Brasil, S.A., 171 F.3d 739, 747 (2d Cir. 1999)).

Besides, the fraud exception is a “narrow one” because of the need to protect the smooth operation of international commerce (See Archer Daniels Midland Co. v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., No. 11 Civ. 0988 (JSR), 2011 WL 855936, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 8, 2011)).

The English courts take the same position regarding the narrow interpretation of the fraud exception. They will not restrain the payment unless the fraud and the applicant’s knowledge of the fraud are “very clearly established” ( See Edward Owen Engineering Limited v. Barclays Bank International Ltd. [1978] QB 159.).

According to the holdings of the U.S. and U.K. courts, if banks can prove the lack of “colorable basis” to draw on the LC or the draw request “amount to an outright fraudulent transaction”, they can obtain the courts' order to dishonor the credit. Thus, the nominated banks have two methods to invoke the defense based on the fraud exception: to prove the lack of transaction basis of the draw or to prove the intention to defraud.

Where North Korea's deceptive shipping practices are involved, it is difficult and maybe impossible for the banks to fulfill the above-mentioned burden of proof. The fraud exception is not very helpful.

2. Illegality Exception and “Social Contract”

The illegality exception is more controversial than the fraud exception. In the U.S., the UCC article 5 expressly states that fraud and forgery are exceptions to the Independence Principle without mentioning the illegality exception. Based on that, some scholars argue that the U.S. law does not recognize the illegality in the underlying transaction as an exception because of the absence of express provision.

Some disagree with that view and argue that the UCC does not expressly exclude the availability of the illegality exceptions.

All of the above-mentioned debates are based on the illegality of the “underlying contract”. However, the real issue is whether the banks' honor of the LC is illegal. Thus, the illegality of the underlying contract is irrelevant.

If the honor of the LC will break the law, banks have the implied liability of not to honor them. By issuing an LC, banks do not have the immunity to act beyond the law. Although banks have promised to honor the LC obligation, they have the higher-level undertaking to do business legally under the “Social Contract” they have made as a member of the society.

VI. Sanction Clause

In recent years, Banks have used sanction clauses more and more often.

A typical sanction clause of LC intends to give Banks the discretion whether or not to honor their LC undertakings. Some argue that sanction clause is a necessary tool to mitigate the risks of being punished by the government or being sued by the customers.

1. the Enforceability

However, the enforceability of the sanction clauses is in great controversy. Some argue that the sanction clause is not enforceable because it is a non-documentary condition. Section 14-h of UCP 600 provides that “If a credit contains a condition without stipulating the document to indicate compliance with the condition, banks will deem such condition as not stated and will disregard it.”(See § 14 h, UCP 600 ) Accordingly, the sanction clauses should be disregarded as a non-documentary condition.

In 2014, ICC issued Guidance Paper on the Use of Sanctions Clauses in Trade Finance Related Instruments Subject to ICC Rules (“2104 GP”). In this Guidance Paper, ICC recommended banks refrain from using sanction clauses in LCs. In 2020, ICC changed its position and issued an addendum to the 2014 GP. In this addendum, ICC emphasized that sanction clauses should not be used “routinely”. ICC also stated that “Clauses should refrain from including unparticularized references to laws generally.( See Addendum to The Use Of Sanctions Clauses In Trade Finance-Related Instruments Subject To ICC Rules, ICC, May 2020) " The addendum includes several recommended samples of the sanction clause. One is as bellow:

“[notwithstanding anything to the contrary in the applicable ICC Rules or in this undertaking,] We disclaim liability for delay, non-return of documents, non-payment, or other action or inaction compelled by restrictive measures, counter-measures or sanctions laws or regulations mandatorily applicable to us or to [our correspondent banks in] the relevant transaction.” ( See Id. )

In the author’s view, the recommended sample has no material difference from those denounced by the 2014 GP. The wording does not change the nature of a non-documentary condition.

2. Necessity and Helpfulness

Sanction clauses may not be helpful to Banks to win the case against their clients. Moreover, sanction clauses are not even necessary for that purpose. As discussed above, if the honor of the LC will lead to the violation of the law, Banks should stop the payment under their implied obligation. Banks should not be forced to violate the law, even in the world of LCs. With that being said, sanction clause is just an express disclaimer which says “I am not liable for not breaking the law.”

However, the use of the ICC-recommended sanction clause may be helpful to prove Banks’ employment of reasonable diligence to mitigate the risk of helping North Korea.

VII. Conclusion

In conclusion, although the Independence Principle prevents Banks from making any investigation beyond the presented documents, the sanction laws impose duties and liabilities upon Banks. In considering the harsh consequence, Banks should employ enhanced due diligence programs to determine whether the underlying transactions potentially violate the sanction laws. If Banks are sued for dishonoring LCs related to North Korea's sanctionable practices, they can invoke fraud and illegality exceptions as defenses.

Note: The above article does not consist of any legal advice. Should you need any Hong Kong or overseas legal services, please contact the following person of DKL:

MEI Liang

Director of DHH Washington DC Law Office

meiliang@deheheng.com

Head of Overseas Business of DKL

WeChat: Catherine_shixy

Email: catherineshi@deheheng.com

Offices

- Beijing

- Chengdu

- Changsha

- Fuzhou

- Guangzhou

- Haikou

- Handan

- Harbin

- Hangzhou

- Hong Kong

- Jinan

- Nanjing

- Qingdao

- Shanghai

- Shenzhen

- Shijiazhuang

- Taiyuan

- Tianjin

- Wuhan

- Xi'an

- Zhengzhou

- Moscow

- Singapore

- St.Petersburg

- Toronto

- Tokyo

- Washington DC

- Ningbo

- Foshan

- Hohhot

- Chongqing

- Suzhou

- Shenyang

- Nanchang

- Qianhai, Shenzhen

- Kunming